Early this month, the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation celebrated our Eighth Annual Connoisseur’s Dinner at Sotheby’s in New York City. The night’s “Fund a Scientist” auction raised more than $1.1 million in just 10 minutes to support reach by Dr. Jeffrey Cummings of the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health. He is conducting a clinical trial of rasagiline, an FDA-approved treatment for Parkinson’s disease that holds promise for slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. We spoke to Dr. Cummings about his research, his passion for Alzheimer’s, and his experience at the event.

Tell us about yourself.

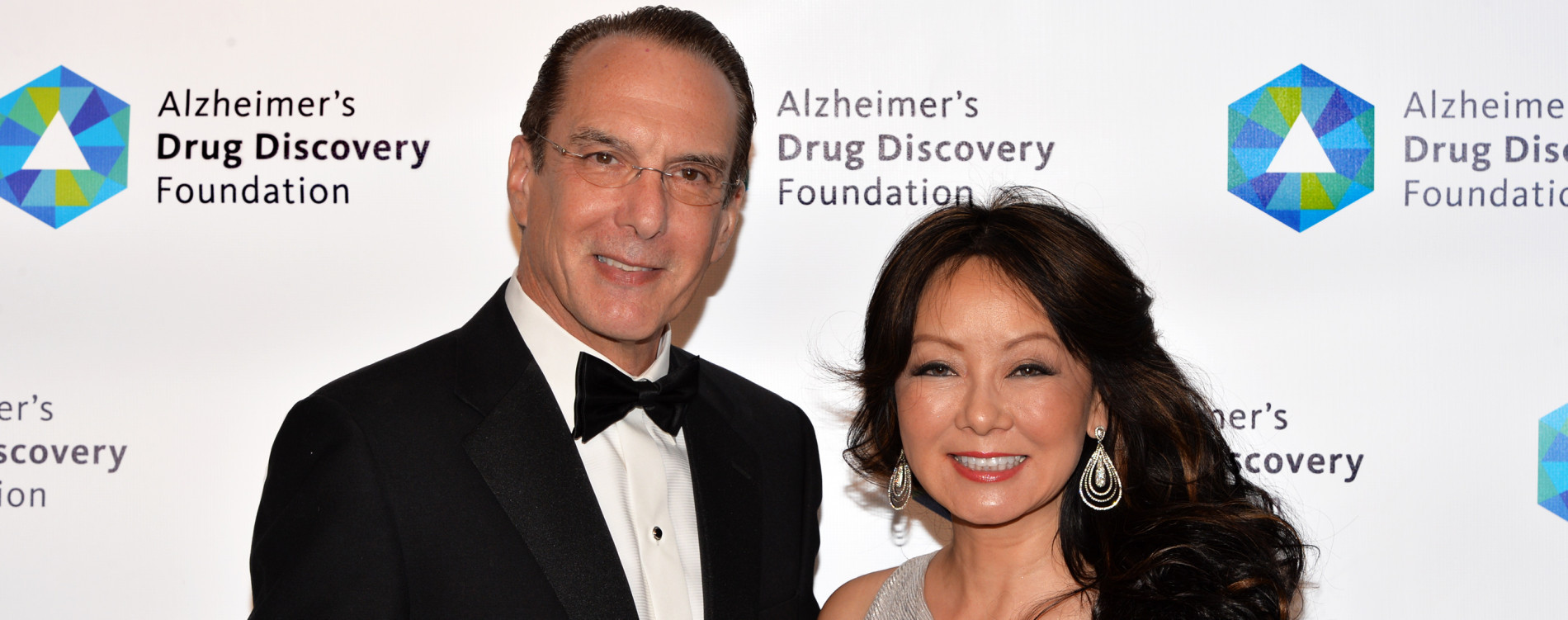

I’m a neurologist who has always been fascinated by the mind-brain interface. I have a wonderful wife and a wonderful daughter. My wife, Kate Zhong, is a geriatric psychiatrist at the Lou Ruvo Center and she directs our clinical trials program. She will lead the rasagiline trial on a day-to-day level.

Why are you so passionate about Alzheimer’s drug discovery?

One of my early mentors, Dr. Frank Benson, was very interested in behavioral neurology and dementia. As I worked with him, I became increasingly drawn to the field. He was a powerful influence.

You’re a practicing neurologist, as well as a researcher. How do patient interactions inform your research priorities?

I’m always trying to integrate new research discoveries into patient care. I’ve had so many influential interactions with patients—in fact, I’ve learned more from patients and caregivers than I ever learned from my professors of neurology.

Are there any experience that stand out?

I had one patient who had a particularly close relationship with his daughter. Quite early in the course [of the disease] she came to him with a matter of the heart and he said, “I’ve gone away.” I found that to be such a powerful way of articulating his experience with Alzheimer's.

What is your relationship with the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation?

Dr. Howard Fillit [the ADDF’s Founding Executive Director and Chief Science Officer] and I have a long history together, going back at least 15 years. We’ve consulted on many of the same projects. Several years ago, he invited me to join the ADDF’s Scientific Advisory Board. More recently, we completed a project investigating repurposed agents—drugs that are approved for one condition but being used for another. We have a shared interest in understanding what repurposed agents doctors are currently using and we have an interest in studying repurposed drugs as a means of accelerating treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Now, we’re collaborating on the rasagiline trial. I have tremendous respect for Howard’s leadership of the ADDF and the catalytic role the ADDF has come to play in Alzheimer’s research.

How did you develop the rasagiline trial with the ADDF?

I had done an extensive review of compounds that might be good for repurposing with colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic, and rasagiline was one of the compounds that emerged from that review. At the same time, Howard had independently begun thinking that it was a good candidate for Alzheimer’s patients.

Why is repurposing an important avenue for Alzheimer’s drug discovery?

Repurposing has the potential to shorten drug development timelines. It usually takes 12 to 15 years to move a compound from basic science observation to FDA approval. We can’t wait 15 years to find a treatment for Alzheimer’s. By using repurposed compounds, you’re working with drugs whose safety, formulation, and manufacturing are already known. You’re down to the critical question: does the drug have efficacy in Alzheimer’s disease.

Why do you believe rasagiline holds promise?

It has been used in Parkinson’s and was shown to improve cognition. We also know from basic science that it has neuroprotective properties that don’t depend on its MAO-I properties. And recently, it has been shown to decrease the production of the Alzheimer’s protein beta-amyloid. If anything, this is a drug that has more promise in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease because it affects proteins central to the Alzheimer’s process.

What makes rasagiline different from other potential Alzheimer’s therapeutics?

It’s a multifunctional molecule, with a neuroprotective effect and an effect on amyloid. We now think that interfering with multiple Alzheimer’s pathways will be critical to the success of an Alzheimer’s drug. Rather than using a combination of drugs, you can use a single drug that has multiple effects.

What do you hope comes out of this clinical trial?

I hope to show a difference in brain metabolism using FDG-PET scans as a primary diagnostic tool, and a trend toward cognitive or functional improvement in patients taking rasagiline [compared with those taking a placebo].

How did it feel to watch a crowd raise more than $1.1 million for your research in under 10 minutes?

It was absolutely exhilarating. To see the kind of commitment that the ADDF had from its donors and that kind of enthusiasm was absolutely fantastic. I couldn’t be more appreciative.

Any predictions about the future of Alzheimer’s drug discovery?

I think it’s unlikely that we’ll find a cure by 2025—the Obama administration’s goal—but it’s a reasonable time frame in which to develop a meaningful treatment. I don’t know if we’re one step away from a new treatment or 100 steps away—but I do know that we have to take the next step. The ADDF has a very thoughtful approach to drug discovery and their work is tremendously important because there are so few organizations funding Alzheimer’s drug discovery and development. Supporting the ADDF is a great way of supporting the development of new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.